I was among the organisers of the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement and received a sixteen-month prison sentence for encouraging people to participate in a seventy-nine-day occupation of key roads in Hong Kong.

Life in prison was challenging. The food was poor, with unbearable heat in the summer and cold in the winter. There were numerous regulations governing prison life, and violations such as sharing food or books or keeping an orange overnight could lead to solitary confinement without access to books, snacks, radio, or television. Inmates were stripped not only of their freedom but also of their dignity, frequently reprimanded by officers and subjected to surveillance cameras.

I promised myself to maintain a clear mind and positive spirit. I viewed the courtroom and prison as platforms to explain our struggle to the public, as the aim of civil disobedience is to raise awareness of injustice through self-sacrifice. I believe a ‘community of suffering’ can evolve into collective resistance against dictatorship.

The anti-extradition protests altered the course of Hong Kong's history but were part of a longer fight for democracy in the region. I will compare them with the earlier democracy movement that began in the mid-1980s and the Umbrella Movement of 2014 regarding leadership styles, strategies, and local identity framing.

Leadership: from collective actions to connective actions

In the 1980s, the push for direct elections of the Legislative Council was under a centralised leadership, primarily led by school principal and politician Szeto Wah, who served on the Legislative Council from 1985 to 2004. The inaugural democracy rally featured a 'chairperson panel' on stage representing various civil society groups, resembling the formal meetings of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

As a student, I was taken aback by this setup. Mr. Szeto, as he later stated in his autobiography, was once affiliated with the Hok Yau Club (revealed in his book as a subgroup of the CPC) but never became a party member. He later founded the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union, which became the most potent teachers’ union in the territory. Szeto employed communist organisational methods to advocate for democracy by establishing strong central leadership, setting up branches and cells in various districts and schools, and recruiting members through services and material advantages.

Younger generations of activists criticized this leadership style as the movement evolved after Hong Kong's handover to China in 1997, arguing that the rigid hierarchy stifled individual creativity and could not engage those outside civil society groups.

From 2003 to 2019, the Civil Human Rights Front organized marches for freedom and democracy on July 1, the anniversary of the handover from British to Chinese rule. The massive turnout of 500,000 people that year, protesting against proposed anti-subversion legislation, highlighted the effectiveness of merging organisational and network mobilisations. A survey indicated only 34.3 percent of participants were motivated by appeals from their organisations, while many joined the march with family (26.6 percent) or friends (45.2 percent), having learned about it through radio or emails. Just 4.7 percent participated alongside other civil society group members.

During the Occupy Central Movement's mobilisational phase in 2013, the leaders known as the ‘Occupy Trio’—Professor Benny Tai, Rev. Chu Yiu-ming, and I—sought to include grassroots initiatives like ‘Deliberation Day’ (forums discussing democracy) and a ‘civic referendum’ (an unofficial vote created by the Occupy Trio for public input on constitutional reform). However, when the occupation escalated in support of the student strike and became the Umbrella Movement, student leaders took charge, with the Occupy Trio and opposition party leaders providing assistance. Internal disagreements over the length of occupation and negotiation tactics between the Occupy Trio and student leaders became so significant that they led to stalemates, leaving the protesters, who occupied the site for seventy-nine days, uncertain due to the absence of clear leadership.

The 2019 anti-extradition protests displayed a far greater flexibility in leadership and strategy, encapsulated in their motto: ‘Be water’. Rejecting centralised leadership, they developed their objectives and methods through an online forum, with decisions made and communicated via Facebook, Telegram, and other apps.

Instead of occupying a specific location for an extended period, protesters formed human chains, sang the newly composed protest anthem ‘Glory to Hong Kong’ in locations such as shopping malls, and staged unscheduled demonstrations during lunch hours in various business districts. These dispersed mobilisations proved to be remarkably effective and challenging to suppress, especially since no clear leaders were identifiable.

Strategies: from legal, peaceful protest to mixed strategies

Prior to the Umbrella Movement, the pro-democracy movement conducted protests solely within legal frameworks, seeking police permission for rallies and marches.

The Umbrella Movement marked a pivotal shift towards the concept of civil disobedience, involving law

The lives of Africans in Guangzhou have been adversely impacted by China's stringent visa and residency regulations, as well as police oversight. This includes direct visa checks that could result in deportation, and indirect monitoring in shopping malls where Africans conduct business, the hotels they occupy, and the community committees in their residential areas. The majority of African importers possess thirty-day tourist visas or visitor visas that last one to two months, which are inadequate for placing orders, waiting for factory deliveries, and managing shipping processes. Only a small percentage have managed to secure longer residency permits (up to one year) to operate cargo businesses or stores in China. Some individuals are residing there illegally, either on fraudulent visas (sometimes issued by deceitful visa agencies) or by overstaying due to a lack of funds to purchase a return ticket.

As US TikTok users seek solace in an alternative Chinese app named Xiaohongshu, we explore the app's background, its distinctive features, and its growing global impact.

Chinese digital nationalism is experiencing a notable rise. A significant indication of this is the increasing public interest in cultural heritage across the nation, particularly among younger generations. They showcase their passion through the enthusiastic purchase of heritage items, such as traditional Hanfu 汉服 fashion, which includes the classic skirt known as mamianqun 马面裙 and the cheongsam, a widely recognized women's dress style from the early 20th century, also referred to as qipao. As reported by Alibaba’s digital marketing platform, in January 2024, sales of mamianqun rose by nearly 25 percent, while cheongsam sales increased by over 31 percent.

China boasts a significant level of linguistic diversity, with 281 languages belonging to nine different language families. However, the distribution of speakers among these languages is highly uneven. Of its total population exceeding 1.4 billion, 91.11 percent are Han Chinese who communicate in Putonghua and/or other Sinitic languages; the remaining 8.89 percent comprises non-Han Chinese or minority ethnic groups who speak an additional 200 languages.

Thank you for engaging with the China Story. The moment has arrived for us to part ways. The website will cease updates starting February 2025.

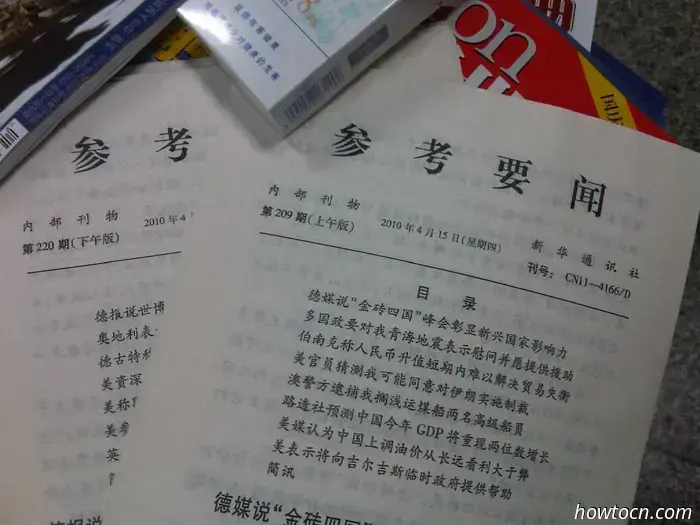

A common saying regarding communist regimes is that their leaders tend to overlook the intelligence provided to them. Martin Dimitrov explores the different internal reference materials under Xi and asserts their ongoing importance. In China, similar to other communist regimes, there are two categories of media: one that is publicly available and another that is restricted, accessible solely to regime insiders with the necessary clearances. This second category, referred to as neibu 内部 or 'internal circulation,' has not been as thoroughly examined by scholars.

I was one of the organizers of the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement and received a sixteen-month prison sentence for encouraging people to participate in a seventy-nine-day occupation of major roads in Hong Kong. Life in prison was challenging. The food was poor, and the summer heat was unbearable while winters were excessively cold. There were numerous regulations governing prison life. Sharing food, books, or even keeping an orange overnight could lead to punishment through solitary confinement, where one would have no access to books, snacks, radio, or television. Inmates were stripped not only of their freedom but also of their dignity, frequently scolded by guards and monitored naked by surveillance cameras.