Government digitization efforts around the globe are often criticized for exceeding budgets, being delayed, and failing to meet expectations. China is not an exception to this trend. Numerous headlines worldwide have asserted that the Social Credit System will oversee every aspect of citizens' lives. However, these claims have seldom been reflected in reality. The Social Credit System primarily does not use scores, is digitally fragmented and quite incomplete, and emphasizes economic actions rather than political or social behaviors. Nonetheless, even this more restricted version of the Social Credit System appears to be hampered by common issues seen in governmental IT projects globally: ambiguous goals, insufficient funding, and internal conflict.

A plan lacking direction

The social credit initiatives in China began over twenty-five years ago as authorities and businesses sought solutions to issues such as the prevalence of counterfeit goods, a triangular debt system where A loans to B, B to C, and C back to A, creating a cycle of bad debts that threaten financial stability, and widespread lawlessness. For years, the central government and multiple ministries have worked to establish data-sharing protocols among traditionally siloed government entities, along with blacklists aimed at punishing serious offenders and promoting ‘trustworthy’ behavior. In 2011, then-premier Wen Jiabao noted that ‘good social credit’ is essential for businesses, institutions, and individuals to thrive in society, while decrying rampant ‘commercial fraud, counterfeiting, false reporting, and academic misconduct.’

The Social Credit System that developed was not solely focused on financial credit. It centered on regulatory compliance, or the ‘credibility’ of businesses. The term ‘social’ was intended to distinguish it from a ‘national credit system’, which was the original concept. The shift from ‘national’ to ‘social’ in 2002 highlighted that the system was to be constructed by ‘society’ rather than the government. Ultimately, the Social Credit System was never designed to be a fully unified framework; at its best, it remains a disconnected collection of various systems, primarily sharing the goal of enforcing compliance with laws and regulations.

The effectiveness of the Social Credit System in achieving its intended outcomes remains questionable. Over the years, the numerous plans put forward failed to address the core question: what constitutes social credit, and what is its ultimate aim? In 2019, researchers asked local officials in China about the Social Credit System, only to receive the response: ‘I really can’t figure it out. Is it possible that you scholars can tell me?’

Numerous experiments were conducted across various domains, yet a common understanding was entirely absent. Beginning in the early 2010s, some localities tested scoring citizens based on criteria such as whether they argued with neighbors or lit fireworks at restricted times, with volunteers, not AI, performing the scoring. Other local initiatives aimed to penalize individuals for eating on the subway, enforced by local transit officers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, certain cities blacklisted individuals for not wearing masks or refusing to get tested. These actions were all branded as part of the Social Credit System, but were rarely integrated or widely adopted.

Private enterprises were also engaged in experimentation. In 2015, Alibaba’s subsidiary Ant Financial launched Sesame Credit, aiming to discover alternative methods for assigning financial credit scores, as many citizens lacked credit cards or extensive credit histories. Sesame Credit utilized big data to monitor citizens’ shopping behaviors, translating this into a three-digit score. An Ant Financial executive indicated that consumers buying beer could be perceived as less ‘trustworthy’ than those purchasing diapers, or that playing online games might reduce one’s score. Scores were also influenced by users' friends, with 5 percent derived from the aggregate scores of one’s network. However, China's central bank, the People’s Bank of China, ultimately disapproved the scheme, which saw Alibaba acting as credit assessor, loan provider, payment service, and marketplace all at once. Sesame Credit incentivized customers for shopping with Alibaba but did not function effectively as a credit-scoring system. In 2017, the bank refused Sesame Credit an official credit license. Although Sesame Credit continues to exist, it performs few meaningful functions and remains entirely voluntary.

Such initiatives lingered on the periphery of the system. The system's primary focus lay in enforcing adherence to regulations. Authorities across China created blacklists for individuals and companies that severely violated laws within the market economy. Violations included fraud, illegal pollution dumping, and manufacturing substandard medications. Regulators could add violators to these blacklists manually, intending to share them with government agencies and the public online. Currently, at least ten million citizens find themselves on such blacklists, facing severe repercussions: depending on the blacklist, some may be restricted from traveling by plane or high-speed rail, while others risk losing government subsidies, professional accreditations, or loans. Given the focus on punishing wrongdoers, it took central authorities twenty years (until 2019) to seriously promote 'credit repair', which entails allowing

-Science-Fiction-The-China-Story.png)

In April 2024, Nymphia Wind, a drag queen from Taiwan, made history as the first East Asian winner of RuPaul's Drag Race. Clips of her in a shimmering golden outfit gained widespread attention online, bringing Taiwan into the global media spotlight and establishing her as a kind of queer representative for Taiwanese authenticity to the world. As she humorously noted, this role can be compared to a wai jiao guan 外焦官 – ‘external banana official’, a play on words with the term for 'ambassador' 外交官.

Chinese digital nationalism is experiencing a notable rise. A significant indication of this is the increasing public interest in cultural heritage across the nation, particularly among younger generations. They showcase their passion through the enthusiastic purchase of heritage items, such as traditional Hanfu 汉服 fashion, which includes the classic skirt known as mamianqun 马面裙 and the cheongsam, a widely recognized women's dress style from the early 20th century, also referred to as qipao. As reported by Alibaba’s digital marketing platform, in January 2024, sales of mamianqun rose by nearly 25 percent, while cheongsam sales increased by over 31 percent.

Thank you for engaging with the China Story. The moment has arrived for us to part ways. The website will cease updates starting February 2025.

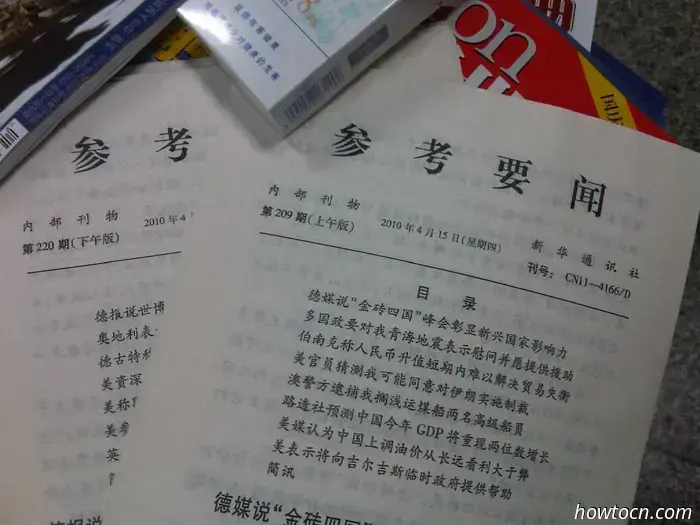

A common saying regarding communist regimes is that their leaders tend to overlook the intelligence provided to them. Martin Dimitrov explores the different internal reference materials under Xi and asserts their ongoing importance. In China, similar to other communist regimes, there are two categories of media: one that is publicly available and another that is restricted, accessible solely to regime insiders with the necessary clearances. This second category, referred to as neibu 内部 or 'internal circulation,' has not been as thoroughly examined by scholars.

In April 2024, the Taiwan Constitutional Court conducted a hearing regarding the potential violation of constitutional human rights guarantees by the death penalty. On September 20, it decided to maintain the death penalty, introducing some new safeguards for its application. Although a coalition of abolitionist non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and research institutions, spearheaded by the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty (TAEDP), has spent twenty years campaigning for its abolition, numerous polls have consistently shown significant public resistance to eliminating the death penalty.

As US TikTok users seek solace in an alternative Chinese app named Xiaohongshu, we explore the app's background, its distinctive features, and its growing global impact.

China's social credit initiatives originated twenty-five years ago, as officials and companies aimed to address issues such as the prevalence of counterfeit goods, triangular debt situations—where A lends to B, B lends to C, and C lends back to A, resulting in a stalemate of problematic debts that jeopardize financial stability—and a general lack of respect for the nation's laws and regulations. As a result, the central government and multiple ministries dedicated many years to creating data-sharing frameworks among typically segmented governmental bodies, along with establishing blacklists to penalize substantial offenders and incentives to encourage 'trustworthy' conduct.