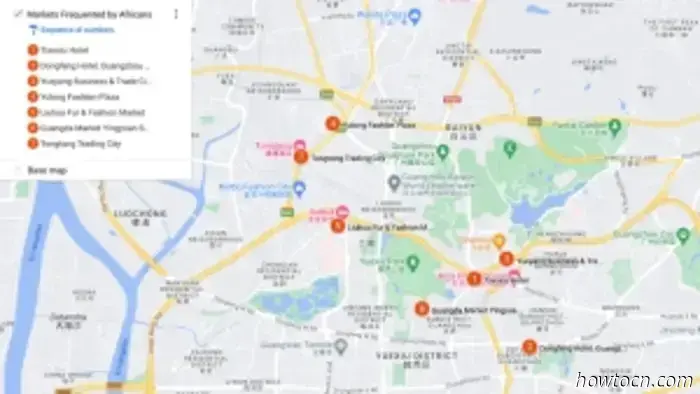

With a population of 1.4 billion, Africa's number of inhabitants is comparable to that of China, despite the continent being roughly three times its size. Africa comprises fifty-four countries and has the most diverse array of languages globally. This diversity is evident among African individuals traveling to and residing in Guangzhou, a trading port located in southern China. In 2018, we conducted a survey with about 120 Africans in Guangzhou, who hailed from thirty different countries.[1] The majority were traders acquiring inexpensive manufactured products to transport back to their home nations. Various trading hubs in the Yuexiu and Baiyun districts draw many Africans, largely due to the convenient proximity of factory outlets, affordable hotels, and informal housing (see figure 1). These factory outlets, which offer goods from the Pearl River Delta and other provinces—including electronics, clothing, footwear, cosmetics, and building supplies—play a crucial role in transporting manufactured goods from China to Africa. The thriving trade spurred by African demand even saved some shopping centers owned by Chinese from being demolished in the early 2000s.[2]

Figure 1: Trading centers frequented by Guineans in Guangzhou

Africans living in Guangzhou have faced negative impacts due to China's stringent visa and residency regulations, as well as police oversight—either through direct checks of visas that could lead to deportation or via indirect surveillance in malls where Africans conduct business, hotels where they stay, and neighborhood committees where they reside. Most African importers operate on a thirty-day tourist visa or a visitor visa lasting one to two months, which is inadequate for them to place orders, wait for factory deliveries, and supervise shipping. Only a small number have obtained longer residency permits (up to a year) to manage cargo businesses or shops. Some individuals are in China illegally, whether on forged visas (sometimes issued by dishonest visa agencies) or by overstaying due to insufficient funds for a return ticket.

Illegal immigration or overstaying, alongside worries about criminal activities like drug trafficking,[3] have brought increased police attention to Africans, particularly since the 2013 immigration law aimed at tackling the ‘three illegals’: illegal entry, illegal residency, and illegal work.[4] The commercial areas of Xiaobei 小北 and Guangyuanxi 广园西, which have high concentrations of Africans, are heavily policed (see figure 2). Police frequently stop Africans to verify visas and residential permits often in an attempt to extort money, which has reportedly become a profitable scheme for underpaid local officers.[5] In 2009 and 2012, there were protests against police raids and racial profiling of African-owned businesses. The latest confrontations between the police and the African community occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, as detailed further down.

Figure 2: Police checking the documents of Africans in a business area

Not all African communities have been equally affected by police monitoring and control. A seasoned worker from a Chinese NGO, who acts as a mediator between the Immigration Department, Foreigner Management Police Stations 外管所, and various African communities, noted that Chinese authorities are more stringent with Nigerians, viewed as ‘troublesome’, compared to other Africans, such as Malians and Guineans, who are regarded as quieter and more peaceful. Furthermore, Gordon Matthews and other authors of The World in Guangzhou: Africans and Other Foreigners in South China’s Global Marketplace have pointed out that some members of other African communities even collaborated with police during raids on Nigerians.[6] The Igbo Nigerians stand out in Guangzhou due to their religious presence (for example, at the Sacred Heart Cathedral), business achievements, interracial marriages with Chinese women,[7] and a history of vocal protests against police actions and the strict COVID policies. They also possess a distinctive political identity and diaspora strategies that differ from those of other African nationals.

‘Troublesome’ Nigerians versus ‘peaceful’ Guineans

We first learned about the Igbo identity through our informant, Achebe (pseudonym), a young Igbo Nigerian who stated that his beret symbolizes the indomitable spirit of Biafra, the secessionist movement in Nigeria that began in the 1960s. A Nigerian scholar introduced him to us in 2021, subsequently guiding us to a small Igbo community of about fifteen men working in a warehouse obscured behind a row of stores selling leather goods and luggage. Inside the warehouse, boxes were stacked high within office cubicles (see figure 3). The sharp sound of duct tape being torn was combined with greetings spoken in Igbo. During our visit, Guangzhou police frequently patrolled the area, passing by Africans in the narrow corridor between the cubicles, fostering an atmosphere of mutual disregard.

Figure 3: Sealed cargo boxes being shipped to West Africa from a warehouse

Daddy Obi arrived in China three years ago to take over a shop from a friend. His previous role as an elder in a village council has smoothly transitioned him into a consultant

Thank you for engaging with the China Story. The moment has arrived for us to part ways. The website will cease updates starting February 2025.

China's social credit initiatives originated twenty-five years ago, as officials and companies aimed to address issues such as the prevalence of counterfeit goods, triangular debt situations—where A lends to B, B lends to C, and C lends back to A, resulting in a stalemate of problematic debts that jeopardize financial stability—and a general lack of respect for the nation's laws and regulations. As a result, the central government and multiple ministries dedicated many years to creating data-sharing frameworks among typically segmented governmental bodies, along with establishing blacklists to penalize substantial offenders and incentives to encourage 'trustworthy' conduct.

Chinese digital nationalism is experiencing a notable rise. A significant indication of this is the increasing public interest in cultural heritage across the nation, particularly among younger generations. They showcase their passion through the enthusiastic purchase of heritage items, such as traditional Hanfu 汉服 fashion, which includes the classic skirt known as mamianqun 马面裙 and the cheongsam, a widely recognized women's dress style from the early 20th century, also referred to as qipao. As reported by Alibaba’s digital marketing platform, in January 2024, sales of mamianqun rose by nearly 25 percent, while cheongsam sales increased by over 31 percent.

China boasts a significant level of linguistic diversity, with 281 languages belonging to nine different language families. However, the distribution of speakers among these languages is highly uneven. Of its total population exceeding 1.4 billion, 91.11 percent are Han Chinese who communicate in Putonghua and/or other Sinitic languages; the remaining 8.89 percent comprises non-Han Chinese or minority ethnic groups who speak an additional 200 languages.

-Science-Fiction-The-China-Story.png)

In April 2024, Nymphia Wind, a drag queen from Taiwan, made history as the first East Asian winner of RuPaul's Drag Race. Clips of her in a shimmering golden outfit gained widespread attention online, bringing Taiwan into the global media spotlight and establishing her as a kind of queer representative for Taiwanese authenticity to the world. As she humorously noted, this role can be compared to a wai jiao guan 外焦官 – ‘external banana official’, a play on words with the term for 'ambassador' 外交官.

I was one of the organizers of the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement and received a sixteen-month prison sentence for encouraging people to participate in a seventy-nine-day occupation of major roads in Hong Kong. Life in prison was challenging. The food was poor, and the summer heat was unbearable while winters were excessively cold. There were numerous regulations governing prison life. Sharing food, books, or even keeping an orange overnight could lead to punishment through solitary confinement, where one would have no access to books, snacks, radio, or television. Inmates were stripped not only of their freedom but also of their dignity, frequently scolded by guards and monitored naked by surveillance cameras.

The lives of Africans in Guangzhou have been adversely impacted by China's stringent visa and residency regulations, as well as police oversight. This includes direct visa checks that could result in deportation, and indirect monitoring in shopping malls where Africans conduct business, the hotels they occupy, and the community committees in their residential areas. The majority of African importers possess thirty-day tourist visas or visitor visas that last one to two months, which are inadequate for placing orders, waiting for factory deliveries, and managing shipping processes. Only a small percentage have managed to secure longer residency permits (up to one year) to operate cargo businesses or stores in China. Some individuals are residing there illegally, either on fraudulent visas (sometimes issued by deceitful visa agencies) or by overstaying due to a lack of funds to purchase a return ticket.