At times, it appears that the prevailing color in Beijing is "Socialist Taupe," with the streets, bricks, and roads all blending into shades of gray and beige. Escaping this muted palette can be quite challenging.

This situation was not always the norm. During imperial times, architects and builders used five vibrant colors to enliven their designs: red, yellow, blue, white, and (yes) gray. These hues were not merely decorative; each one was linked to an intricate system involving aspects like astrology, metaphysics, food, and medicine known as 五行 (wǔxíng). This framework aimed to describe all phenomena as interactions among five elements: metal, wood, water, fire, and earth. Eventually, these elements became tied to specific colors, which dominated the color scheme in traditional Chinese architecture.

There are indications that the Beijing Municipal Government plans to establish a standardized color scheme for buildings and signage in the city, limiting new constructions and historical restorations to (you guessed it) red, yellow, blue, white, and gray.

Dr. Donia Zhang, a Chinese-Canadian author and scholar who is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Chinese Architecture and Urbanism, notes, “Green, red, white, gray, and black have historically been linked to traditional Chinese architecture, such as the Beijing siheyuan (courtyard houses). The outer walls of these courtyard homes were generally made from gray bricks, with structural columns often painted in vermilion red – symbolizing fire and blood, and representing good fortune and prosperity – and window frames colored in green, signifying plants and growth."

Red

Red has held significant meaning in Chinese culture for a long time (Mao certainly benefited from this revolutionary color choice). Traditionally, red symbolized warmth and the highest degree of yang energy, as in the yin-yang philosophy. Its association with auspiciousness explains why red features prominently in weddings, New Year celebrations, and various other important occasions. Consider the 红包 (hóngbāo) "red envelopes" distributed to children during the Lunar New Year or those messages sent by someone intoxicated late-night in a random WeChat group.

Yellow

Yellow was another key color in historic Beijing, primarily associated with the emperor. It was linked to the element of earth and represented the very foundations of ancient Chinese civilization. The Yellow Emperor is regarded as the mythological progenitor of the Chinese nation, and archaeologists trace the earliest examples of a distinctly Chinese civilization to the Yellow River Basin. The river itself receives its name from the color of its water, which turns yellow due to the loess soil found in central China.

In Beijing, yellow plays a significant role in the architecture of the Forbidden City and other imperial buildings. Most imperial palaces, including the Confucian Temple, feature roofs made of glazed yellow tiles. Yellow was also the color of imperial attire, and many palace interiors were coated with yellow clay sourced from Hebei province. The color was so closely linked to the emperor that regulations dictated it could only be used for imperial palaces, temples, and tombs.

However, not all structures in the Forbidden City showcase the iconic yellow tiles. The Hall of Literary Splendor (文华殿, wénhuá diàn), located on the eastern side of the Forbidden City, once served as the imperial library and features a black roof. Similar to other colors, black is connected to an element—specifically, water—which is beneficial for preserving rare books in an environment where fire posed a constant threat.

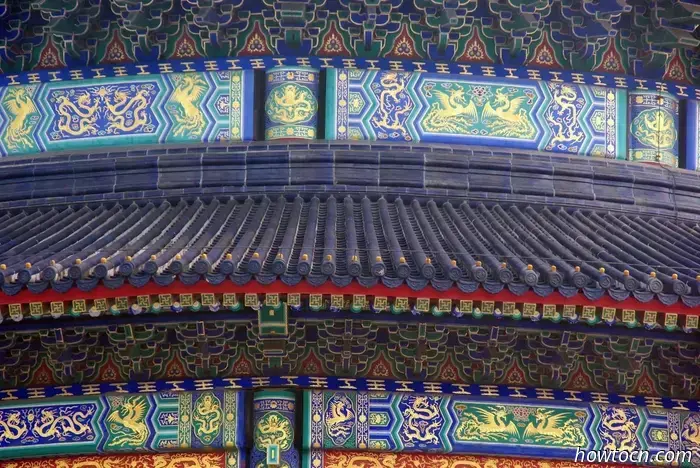

Blue

Blue symbolizes heaven and divine blessings, with the deep cobalt tiles of the Temple of Heaven serving as its prime illustration. This association has evolved over time; initially, when the Temple was first constructed during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), many of its structures had green rooftops. This changed during renovations commanded by the Qianlong Emperor in the 18th century. Notably, the renowned triple-tiered Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests (祈年殿, qínián diàn) once featured a blend of symbolic colors: the first tier was green for the earth, the second was yellow for the emperor, and only the upper tier, representing heaven, was adorned with blue tiles. After remodeling by the Qianlong Emperor and later following a fire in 1889, all tiers were uniformly covered in blue tiles.

Concerning the municipal initiative to limit future construction to a palette of five colors, Dr. Zhang finds the proposal to have merit. "In the Daoist classic Dao De Jing, the Chinese sage Laozi noted that 'Colors blind the eye...' (verse 12); he suggested that excessive colors are not beneficial for human vision. In architectural education, we were also instructed that no more than three primary colors should be used for a facade design to avoid an appearance that is overly busy and chaotic. This philosophical perspective and artistic concept may help elucidate the

These colors were linked to an intricate framework that encompassed a wide range of topics, including astrology, metaphysics, as well as food and medicine.